I write about things I notice here and there, some of which do not always make for polite conversation

Wednesday, November 12, 2008

And it doesn't really help that the only work of literature that I have read of late ( discounting yet another Jeeves) is a mind-numbingly boring saga of a female model (you really have to qualify these things nowadays), who wants to "trade up". I've covered almost 2/3rd s of the book, painstakingly giving the protagonist, (who is as lost as the plot itself) a chance to find herself, and in the process steer the book into a direction, any direction. But sorry Ms Candace Bushnell: you, your book AND your heroine make absolutely no sense to me, and hence, you have the rare distiction of being one of the 2-3 authors who have succeed in boring me so much so as to make me chuck a book before I finished it. This in over 16 years of my stint an enthusiastic reader, with hopefully many more years to come (there's no reason why not, unless I die or something as drastic happens. On second thoughts, if they keep on writing more stuff like this, I might do a 180 degree turn and transform into a book-hater).

Trading Up is a literary atrocity. To all those who have not read it, here's a word of advice-it just might make more sense to go out into the heart of a desert and try to find your way back blindfolded, than to find direction, any semblance of direction, in this book. And it did come as a bit of a shock, coming from the author who gave birth to Sex and the City.

The blurb makes a parallel between Bushnell and Jane Austen, as both of them "skewer" the societies that they know so well, and belong to. Sorry again. If you are an author, and do not know any other society than the mind-numbingly dull one that you belong to, then you are either lazy, or dumb, or just trying to make easy money by safely using, or trying to use, the tried, tested, and done-to-death formula of a young girl, a rich man and love, or lack of it.

And while I am at it, might I also say that the blurb's parallel to Austen does not, for me, bring Bushnell up to the former's level? It however, certainly trades Austen to Bushnell's class, and in a way, makes me happy that some people do acknowledge, albeit unwittingly, what I have been saying for some 5 years now. That reading Austen is just like watching one of those soap operas-set in some shire in old England. I mean, cummon: ALL her stories have just one theme: how the pure, naive, virginal (and not only physically, but metaly as wel), unscheming, young, pretty woman manages to marry the best man. And by "best", I mean a man who's rich,tall, silent, honest, unvirginal (again, also in thoughts) and not-so-young, in that order.

Phew! Having one's own blog does help.There, I have said it! Ever since high school, when I was first introduced to Ms Austen, I have dislike her works, but have tolerated her, for fear of making some literary sacrilege by voicing my discontent. No more. Austen, Bushnell and ALL others who have ever written on the same lines and are planning to do so, here's a word of advice: Write for one of the inumerable women's magazines that sell so well (and I read so often). And at least those mags are honest in what they do, unlike you, who try to pass on your inanities under the title of "a novel". So, readers know what to expect, and can be spared the shock of sifting through pages and pages of boredom in the hope of finding something that would make it all worthwhile and yet finding none.

No, I'm not turning into a cynical feminist. Trust me. You have be as much a book lover as I am, and then go through the ordeal of Trading Up to appreciate my reaction.

And speaking of reactions, I found out, the hard way, that making those available to the public in the raw form as and when it occurs to you has a LOT of disadvantages. Specially when you are young/ junior/ new to the city. Controlling one's temper and distilling those feelings before sending them to the public domain is the one great necessity of civic life.

If only it were not as necessary-- if only we could spit out "Your banter is killing me" every time your long-lost relative grills you about your single and carefree life, if only we could say "No" everytime you were asked "do I look good?", and if only you could say "It's so flat I would rather do it by myself" everytime your current girl/boy friend wanted to sack it out with you...if only!!

The sheer number of people I know, who are, right at this moment, dying to say exactly those same things in reply to exactly those queries would easily exceed the number of fingers on my hands.

But let me not put ideas into your civic little heads. No. I am NOT propagating uncivility, and DEFINITELY not asking people to suddenly wake up to be Epitomes of Rudeness. All I ask for is a little degree of honesty, coupled with a little less obsessiveness to be "prim and propah".

Trust me, that works wonder. Like the hand-made softboard in my flat, which has its own charm that comes from the torn, used, newspapery look. Which a velvet-covered structured board would never have. Which would be prim, but not "lived-in", and which would give my wall an impersonal, office-like look.

Let us not be velvety softboards. Let us be the hand-made variety- with some having news-paper covers, some having a brown paper cover, while others drape themselves in coloured marble paper! (mind you, I didn't say "no cover at all" :) ) And in being so, let us be a part of the whole, and yet retain our individualities.

Let us, for once, learn to say NO-in the right places.

Huh! There, I have rambled again. Well, see you then. You run along, while I rejoice- I can still write, after all!

Monday, August 25, 2008

Life and times

Sigh! There’s a reason why God made men and women into two distinctly different sects, and why the likes of Mills and Boons find readers in women even today! I also re-learnt the importance of tact over brute force. A born dance enthusiast, I stepped across the line, danced with the trainer, and ended up finding myself suspended mid-air on his right knee, feet and hands above the ground ( this, besides the oh so regular ;) other acrobatics that we all learnt!!) My body is protesting today (circus after a two-month break you see!), but ask me again, and I’ll partner you right away!!

And how was the not-a-Goliath trainer able to ‘lead’ me to do all of that? By sheer placement of body weight, hands and of course, what I always call ‘the dancer’s intuition. (The catch in these dance forms is that while the man is leading you, you might have no clue as to what he wants to do next (apart from knowing the basics of course: John Travolta will not be able to manage you if you don’t), but you end up doing it nonetheless. No words exchanged, no tugging and pulling, no force applied.

Lesson learnt? I think so: a greater lesson of life too, learnt and to be practiced.

Amid all the dancing and fêting, I also managed to read Khushwant Singh’s Men and Women In My Life, and while the sheer KhushwantSinghism (please excuse that) of the narrative pleased and amused, it turned out to be a disappointing read altogether. It is immensely difficult for me to accept that none of the men he ever met had innate qualities that could match up to even the least mentionable of the women he wrote about. Anyway, apart from the piece on the beggar-maid, it all seemed like an exercise in name-dropping, and a platform for personal vendetta. Well, the vendetta bit might be true strong a word for a book of this calibre, and might not even be close to what he really had in mind when he wrote it, but a reader is entitled to her opinion, right?

I have also taken to watching Sex and the City all over again (this time, in a regular, thorough fashion, thanks to the DVD set I acquired!) And my 23 years somehow makes me appreciate the humour and the acridity in the series much more than when I stole secret shows on the TV. Now come on, don’t get your guns ready…so it’s not top of the line intellectual content, but ever wondered how dull life would be if there was no easy entertainment? Easy on the head and the mind, that is ;) Because, that would mean no Friends and Sex and the City, no Tintin, no long queues to the Phuchka (pani puri to non-bongs, or golgappa) stall, no going over-the-top giggling with friends, no reading Archie comics, no drinking just for fun and dancing barefoot on the floor ;),no teasing your mom just like that, no buying/getting gifts for the heck of it, no oh my god…the list of ‘nos’ is too lengthy for me to put down without suffering a coronary seizure. Plus, it only takes a different approach to find meaning in the seemingly meaningless. But more on that later, when it comes ‘easy’ to me…

Till then, cheers to the seemingly meaningless journey of our lives…and to the hope that we all find meaning quick!

Thursday, August 7, 2008

shesh paatey..the dessert

I wish, too, I could describe the sweetmeats and the sweet and saline "pithas"--concoctions of grain, fruit, milk and sugar or molasses: fish shaped, discus-shaped, half-moan-shaped fluffy cakes of ground or shredded coconut, little hard toothsome balls of crisp brown-baked rice and of the aromatic sesame-seed, the ksheer-stuffed patishapta with a mat-like texture, the brown-and-white rice-cakes which should come from the pan to the mouth, the dumplings of thickened or curdled milk submerged in payesh---a whole domain of chew-ables and lick-ables and suck-ables as one would say in classical Bengali. Wonderful products, these, based on formulas which may differ from district to district and even from family to family, but even these are of lesser importance than widow-style vegetarian food. For it is there--among a community of nun-like women living on one meal a day and observing numerous fasts, that Bengali cooking reaches its height of finesse, in spite of the dietary restrictions ordained, or rather because of them. It is, I think, a beautiful style---beautiful because it is frugal, adroit in the use of edibles generally despised, and is both varied and consistently suave. The humble pumpkin-flower in the kitchen garden, chipped husk of the gourd, stalks of the water-lily, the meanest of sag and vegetables: things like these become delicious when they come from the widows' kitchen. You can taste a lentil pate' which melts on your tongue, the succulent vine of the pumpkin laced with undercooked whole grain, fricassees of the slightly astringent green banana with fleshy smooth slightly sweet roasted jack-fruit seeds, velvety mashed arum touched up with raw mustard-paste and the fragrant green chili---delicacies as rare as Japanese raw fish or the truffle of France. And the rice---you will have no idea of what rice can be until you have tasted the "food-of-the-god" variety [9], served not on china or brass, but on a black stone plate---the only kind permitted to widows. While I am on this subject, I could as well mention a fact from my personal life, which is not without relevance here. I am one of Nature's own flesh-eaters, but my two most memorable meals were vegetarian. The first was at Santiniketan, where my wife and I had gone to visit Rabindranath and were staying as guests of his family. "We could get no fish today---I'm sorry," murmured the poet's daughter-in-law as we stepped into her formal dining room at lunchtime. I confess my first reaction was one of dismay, but as I sat at table and noticed the shapely little mounds of rice, as white and fine as jasmines, laid on jet-black polished stone-plates, I felt it was a special favour that Mrs. Tagore was doing us that day. It was April and already intensely hot in arid Birbhum, but the room was large and cool and dark, the wetted coir-screens on the windows were wafting a mild sandalwood scent in the breeze of electric fans, soft music issued from the radio of which we could see the glowing dial in the half-light, two great Alsatians lay sprawling on the floor, there was our soft-spoken hostess in a buff Orissan sari---and in front of us the cool black stone plates set off by the whiteness of the rice and surrounded by crescents of bowls exuding appetizing flavours: the ensemble was perfect. The special charm of the meal was that sight and hearing and the olfactory organ shared the pleasures of the table, in a sense other than gastronomical. Some years later, on being invited by a West-Bengalese friend to an evening party held in honour of his betrothal in his Calcutta home, I witnessed a ceremony the like of which I had never seen among East-Bengalese families. In the entire Bengali-speaking area, fish is an inseparable part of any feast connected with a Hindu wedding, but this Brahmin family had evidently a different tradition regarding betrothal feasts: the entertainment was pure vegetarian---and a wonder to behold. We---some fifty guests of us --- sat on grass mats or woollen rugs in a long verandah overlooking the inner courtyard of the house; in front of us were red-brown earthen plates and tall glasses of the same material filled with keya-scented water; the food was served in tiny little bowls of which there was apparently an endless series---everything was spotlessly clean and attractive to the eye. I did not count the dishes, but I was told there were exactly thirty-two of them (or maybe sixty-four!)---that being the auspicious number prescribed by tradition. They came in marvellously diminutive quantities, in a fixed order of succession, without a touch of animal substance anywhere, without any meaty vegetables, even---an extraordinary array of greens cooked with mysterious combinations of spices and grains, according to recipes which, I imagine, were among the most complex invented by man. I could not identify all the dishes, and I no longer remember what were the ones I did recognize, nor whether I relished them all, but I must say that this meal---and the vegetarian lunch at the Tagores' residence---are aesthetically the two most satisfying meals I have ever eaten in my life. But all this is a thing of the past. The world I have described in the foregoing pages has been vanishing at a rapid rate since the end of the Second War and the partition of Bengal; it has scant chance of survival after the older generation has passed out. Tremendous changes have occurred in the social pattern, especially in and around Calcutta; conditions have emerged which simply do not permit a time-consuming complicated cookery style. The younger generation of middle-class Bengalis lives in small flats, preferably sans parents; man and wife both go out to work; the domestic help they can get is scanty and irregular. These circumstances, combined with the romantic and ebullient disposition by which Bengalis can be easily distinguished from their compatriots of the north and south, have remarkably altered the food habits of the present generation of Bengalis. Gastronomically speaking, they are exhibiting signs of national and international integration to a far greater degree than any other group of Indians anywhere. Bengalis of my children's age delight in dosas and beef-rolls, thrive on sausages and hamburgers; they frequently eat out or bring home packages from Chinese or Punjabi restaurants, in order to save the trouble of cooking; they have developed a taste for casual meals eaten at odd hours. In this country of abundant fresh food, they are allured by the canned ready-to-eat substitutes which have begun to hit the market; some even prefer instant coffee to that glorious offspring of their native soil---the fragrant leaf nourished by Nature and man on dizzy Himalayan heights--chiefly because the preparation of tea demands more time and labour. Everything, of course, is in order, just in keeping with the times---nobody can deny the importance of minimizing housework in the conditions of today. But if the Bengali culinary art is doomed, as it is clear it is, that is all the more reason why records of it shou1d remain, for changes themselves are subject to change and man is nothing without history and ancestral memories. 1. Of this there are many attestations in Vedic and Puranic literature. 2. Derived from Tamil kari, a meat sauce. The root of the Bengali word tarkari (which is used with a similar lack of discrimination) is Persian tarah, a sag, vegetable, or meat. No dictionary says whether the second half of the Bengali word is related to Tamil. In Sanskrit, the generic term for cooked food (except rice and desserts) is vyanjana, a term of literary criticism denoting effective expression. A vyanjana as cooking term means food which has been made effective by art. This "correspondence" of poetry and cookery was also noted by Baudelaire. 3. I have failed to find an English word for this vegetable. The great Monier Williams defines it as a species of small cucumber (Trichosanthes). I have never seen it outside India. 4. The word primarily means a hoax or camouflage. Lentil-cakes cooked with rich spices resemble a meat-dish in appearance and taste, hence this name. 5. I do not know of any other part of India or the world where milk is turned to casein--the Bengali word is "chhana", and I'm not sure if the English expression is quite accurate. "Chhana" is the base of all the famous creations of the Bengali confectioner. Its nearest Occidental equivalent is cottage cheese. 6. The sag and the shukto are both concoctions of bland or bitter leafy herbs and vegetables--nomenclature depends on the style of cooking "Sag-bhat" is the set phrase for the poor man's diet, also euphemistically used when one invites a friend to a banquet. The first thing served in a wedding feast is a sag. 7. A jelly-like preparation of crushed mustard and spices, sometimes mixed with tamarind or green mangoes. The pure variety is stronger than the mustard Englishmen eat with their beef. 8. "Brinjal" is the Anglo-Indian word for the fruit of the egg-plant, derived from Sanskrit via Portuguese. 9. It may seem paradoxical that this deprived sisterhood should be sanctioned the finest rice. The fact is that most Bengalis prefer parboiled rice whereas the sacerdotal sun-dried variety is enjoined on the widows. Actually, the latter is finer and more fragrant, but is believed to be less nutritious. Of this, however, there is empirical evidence-- the average widow lives until old age in excellent health. p.s : and for all those who have not been initiated to the wonderful realm of bengali food, here's an open invitation: come down to bangalore (or wherever you can find me), and i'll do your haatekhori. What's that, did you say? Find out guys...it's a good initiation in itself!!

To end it all, let me stress on the other inherently bengali bit that is, like so many other things inseparably bangali, on the throes of being lost and forgotten: the bengali chora (limmerick). Like Tagore's songs, there's one for almost all occassion (indeed, the great poet wrote some himself), and has been an inherent part of the growing-up phase for most of us. Sadly, I can't say the same for my kid brother or his contemporaries and youngers. But all this food-talk has, apart from releasing all my gastronomical hormones in full force, also reminded me of this one limmerick that Sukumar Roy, (Satyajit Ray's father, and a great writer by himself), had penned. Alpetey khushi hobe Damodar Seth ki? Moorkir mowa chai, chai bhaja bhetki... and on it goes....(translation unnecessary as the essence lies in the language itself)

Oh, but more on these little bits of literary wonders later... it has been an uncharacteristically long blog!

Cheers!!

some more...the last but one

(contd)

Bangali Ranna contd

In a poem entitled Nimantran ("An Invitation") and addressed to an unnamed lady, the aged Rabindranath imparted a touch of his lyricism to mundane food, albeit half in jest and with a slant on the "modernist poets. "No golden lamps or lutes are available now," (I am giving a rough rendering of the passage.) "but do bring some, rosy mangoes in a cane-basket covered with a silken-kerchief, ... and some prosaic food as well--sandesh and pantoa prepared by lovely hands, also pilau cooked with fish and meat--for all these things become ineffable when imbued with loving devotion. I can see amusement in your eyes and a smile hovering on your lips; you think I am juggling with my verse to make gross demands? Well, lady, come empty handed if you wish, but do come, for your two hands are precious for their own sake." The last two lines lift the poem to a non-material realm, but the reality of the mangoes and pilaus remains undiminished. The novelists know what they are talking about and have all the words at their disposal, but I am now constrained to use a language utterly unsuited to my purpose. In course of my sporadic attempts to translate Bengali fiction into English, I have found the food words the most intractable. There are three possible ways to deal with them: to retain the originals and add explanatory notes, to invent neologisms, or to slur the matter over: none is satisfactory. Generations of Bengali cooks (mostly women) have devised and developed a variety of dishes belonging to the same genre but each with a specific name and distinctive in taste and flavour, all which, to the eternal amusement and irritation of the true-born Bengali, are lumped in Anglo-Indian English in that ubiquitous and imprecise word "curry"[2]. A "dalna" is no more like a "'chachchari" than a horse is like a goat; to label both of them as "'curries" is just like using the term "quadruped" when the goat or horse is meant. "Payasanna" is generally rendered by Sanskritists as "rice-pudding", but "'anna" means any kind of food, and Bengalis cook their payesh also with semolina or vermicelli or casein balls. It would take a dozen English words to distinguish between "amsattva" and "amshi" (both products of mangoes), or between the thick ginger-flavoured "chatni" and the bland liquid "ambal", both sour-based desserts. It's a pity one must use "lentil-cakes" for both "daler bara" and "daler bari", for they differ not only in size and shape, but also in the technique of preparation and their use in cookery. Even that dailiest of daily items, "machher jhol", remains inexpressible in English; to translate it as "fish curry" is an insult to Bengali culture, and that is the only word available. I have often been appalled by the limitations of Bengali vocabulary, which does not permit us to name al1 the shades of colours or parts of the human body except with the aid of Sanskrit words seldom used in conversation. But, now that I come to think of it, I realize that my native tongue has a marvellous array of food words--single words, I mean, unadorned by any of those adjectival or descriptive phrases which constitute the glamour of a French menu. A dish of spiced potatoes may be called by no other name except "dam", but if you add sweet pumpkin, it at once becomes a "chhaka". "Dolma" is an exclusive term for stuffed patols [3], just as "dhoka" [4] is reserved for fried lentil-cakes served in a thick gravy. No one knows why this is so, but such are the ways of the language; evidently the Bengalis have a passion for affixing a new name to every creation of their kitchen--even where the dishes are variations on the same theme. The "ghanta" and the "chachchari", for example, are both pot-pourries, both composed of vegetables plus chipped fish or fish-bones, or of vegetables only; the only difference seems to be that a chachchari may be cooked with mustard and a ghanta may not. Yet another variety of pot-pourri is the "labra" which, being a favourite of the Vaishnavas and served in their ritual feasts, mustn't ever be contaminated with animal products: according to one lexicographer, it is a hash of six vegetables--the trunk and the flower of the banana, sweet pumpkins, kidney beans, radishes, and brinjals. Likewise there are many variants of the so-called "fish-curry", of which the most common are the "jhol", and the "jhal" or "kalia", distinguished by their relatively bland or sharp taste. Cooking styles are determined by the size, the flavour, and the texture of the fish; each one of the numerous varieties eaten in Bengal has appropriate spices and vegetables assigned to it--special techniques have been devised for dealing with the smallest kinds. There are even specialties prepared with only one particular kind of aquatic food, such as the "dai-machh", which is really "it" only when the fat part of a mature rohit is cooked in sour curd with cinnamon and raisins, or the "muthia" (an emanation of East Bengal), of which the only possible base is the lean part of the chital.

(contd)

Friday, August 1, 2008

Bengali food!! ;)

At that, I smiled inwardly: having no data to support the claim, nor any inclination to refute it, that was the best I could do. But that was when all my neccessities in the gastronomical direction would be taken care of by Ma.

Then, during my student days, another friend told me, 'If you don't know how to cook, you are no gourmand!' (This I may still contest, but I did eventually learn, and come to like cooking, and have to accept the simple fact that the general appreciation of good food increases by almost 10-fold when you appreciate the method of making it.)

But the point here is, as people who know me already know (there is no way they can't know this if they claim to know me!), if you share a fraction of the enthusiam that I have for good food, you will enjoy the article below.

DISCLAIMER: This one revolves only around that inimitable cuisine: bangali ranna. However, it does not mean there is any less appreciation for the numerous other varities of dishes that the other parts of the country/world has to offer. It's simply like this: anyone who's a true Bengali at heart also invariably shares a liking that almost borders on a passion for the dishes and cooking style of Bengal. It is genetic, and very little can be done about it, as for us Bengalis, food is not for subsistence, it is a way of life.

Am pasting an article that I came across on the net, one lazy day when I was surfing the net to better my skills as a cook. The article was written by Budhdhadeb Bose, and had been translated by the author himself from the original Bengali Bhojon-shilpi Bangali. The translation has been published in the daily newspaper The Hindusthan Standard of Calcutta. The Bangla article, first titled "Bhojan-Bilasi Bangali" but later changed to "Bhojon-shilpi Bangali" appeared in 4 daily installments in the Ananda Bazar Patrika of Calcutta, during January 1-4, 1971. Recently, in 2004, this has been published in book form by Vikalp, Kolkata.

THE ARTICLE:

There is no such thing as "Indian food"; the term can only be defined as an amalgam of several food-styles, just as "Indian literature" is the sum-total of literatures written in a dozen or more languages. And I think it is no less difficult for Indians to eat each other's food than speak each other's tongues; an "Indian" dinner which a Tamil and a Sikh and a Bengali can eat with equal relish, is more of a dream than reality. This point was curiously brought home to me on one occasion during my travels in America. I had arrived rather tired after a jerky flight at some little university town; meeting me at the airport my sponsor told me with a smile that he had arranged for me an Indian meal with an Indian family. "I am sure it would be very much to your liking," he added. I at once asked, "Which part of India do they come from?" The professor did not know. The upshot of it was that I spent the night hungry, having been unable to consume anything except a few spoonfuls of plain rice and a cup of coffee at the table of the charming Tamil family, where the professor had piloted me from the airport. I hasten to add that no offense is meant to my gracious host of the evening, nor do I think I need apologize for my provincialism. I have seen high-born South Indian ladies ready to faint at the fishy odour issuing from a Bengali kitchen. It's a case of the fox and the stork, and you can't do anything about it Certain varieties of Indian diet are mutually exclusive.

We cannot be sure whether there was ever a standard diet for the whole of India--available records are meagre, and no gastronomic counterpart of the Kamasutra is in existence. All we can guess on the basis of literary evidence is that the ancients were a meat-eating, wine-tippling people, inordinately fond of milk-products and beef-eaters as well.[1]The Buddha himself did not impose a ceiling ban on flesh-eating, many of his followers (Bengalis?) ate fish habitually. The only strict vegetarians in ancient India were the Jains--a rather small and relatively isolated community with scant influence on the social life of orthodox sects. How and when both beef and pork came to be interdicted and the great schism between vegetarians and flesh-eaters arose on the Indian soil cannot be ascertained with any degree of precision; we do not even know whether these arose of religious or circumstantial pressure. Nor we can form a clear idea about the type or types of cooking current in the Vedic and epic ages. Homer describes each meal with meticulous care, dwelling on every detail from the slitting of the bull's throat to the hearty appetites of the heroes; but the great sprawling Mahabharata is remarkably--even annoyingly--silent on such points. The phrase randhane Draupadi--`a Draupadi for cooking' has come down to us and is cited to this day, but not once do we see this proud lady actually in the kitchen, not even during the period of exile; the feeding of the wrathful Durvasa and his one thousand disciples was magically accomplished by Krishna, without any effort on Draupadi's part. Bhima, we are told, served a whole year as the chef in Virata's household, but as regards the delicacies he presumably concocted for the royal table, we are left completely in the dark. The Ramayana does a little better; we often see Rama and Lakshmana bringing home sackfuls of slain beasts (wild boars, iguanas, three or four varieties of deer. We are also told that their favourite family diet consisted of spike-roasted (meats) (shalyapakva), known nowadays as shik-kebab or shish-kebab); --unfortunately no other detail is supplied. Who skinned the carcasses or made the fire or turned the flesh on the spit, what were the greens and fruits eaten with the meat or the drinks with which it was washed down--all this is left to our conjecture. Nevertheless, we are eternally grateful to Valmiki for the passage describing the entertainment provided by the sage Bharadvaja to Bharata and his retinue; there is nothing to compare with it in the Mahabharatan accounts of the Raivataka feast or Yudhishthira's Horse-Sacrifice. For once in our ancient literature we find the courses itemized--savoury soups cooked with fruit-juice, meat of the wild cock and peacock, venison and goat-mutton and boar's meat, desserts consisting of curds and rice-pudding and honeyed fruits, and much else of lesser importance. All this is served by beauteous nymphs on platters of silver and gold, wines and liqueurs flow freely, there is dance and music to heighten the spirit of the revels. Granted that the whole account is somewhat fantastical--it was the gods who had showered this splendour on that forest hermitage--a splendour that rivals that of Ravana's palace in Lanka; but this at least tells us what Valmiki thought a royal banquet should be; evidently he had experience of a highly sophisticated culture.

To read the same passage in the medieval vernacular versions is to be transferred to altogether another world--a world hedged in by scruples where the cult of Kama--the pleasure-principle of life, which was highly honoured in the heroic age, had fallen into desuetude and the epic tales were used as vessels of unrelieved piety. In both Tulsidas and Krittivas many details of the original are suppressed or glossed over; in both, the vegetarian bias is strong. Tulsidas vaguely mentions "many luxuries", but lists no more than roots and herbs and fruits; the only drink he names is "undefiled water". Krittivas begins and ends with milk-products. Both poets, living in impoverished rural-agricultural communities, recoil from magnificence and reduce Bharadvaja's feast to a modest meal, which their public would find both tempting and innocuous

It is refreshing to turn from Krittivas to Kavikankan and watch the huntsman Kalketu wolfing his dinner--putting away huge mounds of rice with the aid of crab-meat and one or two leafy vegetables. We almost hear him crunching the crab-shells and spitting out the well-chewn remnants; we admire the authenticity of the remark he flings at his wife: "You have cooked well, but is there more?" Yet we cannot accept this as typical of the daily Bengali fare in Kavikankan's time; the eater's taste reflects his off-track occupation rather than the norm. Bharatchandra's famous line, "May my children thrive on milk and rice" must not be taken literally, for "milk and rice" is a metaphor for prosperity and well-being. It is only in our prose fiction from Rabindranath and Saratchandra down to the present times that we find adequate accounts of what the Bengalis eat, each according to his station in life and individual taste. Menus are often mentioned, variations noted; some lady-novelists have done us the additional favour of describing methods of cooking. Of food as a means of characterization there is a fine example in Rabindranath's novel Jogajog. Madhusudan has made his millions by honest toil, is aggressively proud of his wealth, is fond of vain display, his dinner service is all silver; yet his favourite diet is coarse rice, one of the inferior varieties of dal, and a mash of fish-bones and vegetables. The addition of this little gastronomical detail makes it all the more clear what a "tough guy" the poor ethereal Kumudini has to confront in her new home. On another level food has made its way into Bengali verse--and not merely for comic effects as in Ishvar Gupta.

(contd...)

Friday, July 18, 2008

Realisation(s)

The doctor in the hospital came as a blessing. It is only when you are in need of people that you realise their worth: sad, but very true, as I realised. Had it not been for the Gentleman-Doctor who not only tended to me, but also dropped in a word with the opticians to supply me with a new pair of glasses ASAP, poor me would have been stuck with a watering, red eye, and partially blind ( I did spend a day with one lens on, so you can imagine!!)

On another note, I also learnt of the virtue of patience, being proactive, and the thin line between being proactive and ‘bugging’ (thankfully, this I learnt at someone else’s expense!). Hah! Sorry, can’t divulge too much ;) But yes, trust me: excitement is in active participation and NOT in passive observation. Who said that? Well, my regards to him (ok, or her). A very keen observation of the multitude that we comprise of, and some degree of hurt (or hopelessness?) must have made that come.

Why? Come on….just look around. We have non-playing cricket experts in almost every home in this country, people who have NEVER even tried the first steps of any dancing course judge people on TV with an élan that would beat Saroj Khan or Thankamani Kutti’s, and do I even need to get started on the numerous daily affairs that people will just 'advise'/question you on?

‘Why are you asleep at 12.30 in the noon?’ (Because I work till 4 in the morning!!) Have you ever faced anything like it? Chances are you haven’t, and hence the question in the first place.

Why this, why that, even why do you watch FRIENDS so many times over and over again!!! Because I LIKE TO, that’s why!! (And because its one of the best things ever to come on TV: this opinion of mine is shared by hundreds of people all over the world, across countries, age groups AND levels of intelligence, so it has to hold some weight, no?)

Well well, let’s not end in that grouchy note: here’s something for all of us to laugh at:-

"I heard somebody say, 'Where's (Nelson) Mandela?' Well, Mandela's dead. Because Saddam killed all the Mandelas" , said George Bush, on the former South African president, (who is still very much alive), Washington, D.C., Sept. 20, 2007.

Sigh!! :) :) :)

At this rate, we can all be presidents one day…….

Take care you all!!

Monday, July 7, 2008

Prodigal Blogger ;)

I'm growing incorrigibly infrequent. Not that it matters to anyone, but for all those who have taken the time to go through this chronicle of my musings, its because of a sad mix of lethargy, weird office timings, and a comparitively restricted access to the net. Also, the usual impediments of shifting to a new city, adjusting to a new way of life.

Speaking of which, I should say, my present flatmate has done me a great favour in placing that amazing invention of science and technology, a TV, in the flat. And just in case you you're already thinking, no, I'm not a parasite...we share the cable bill! :) Almost 5 years without the continual presence of the dumbing-down machine had almost turned me into an out-of-touch weirdo who only knew new songs from the radio or the net, and only knew news from the papers...ok, also from the websites. Or so I thought. Now I'm happy for the 5 saved years of my life. :)

The world of the small-screen today amazes me. Everybody is in a rush to bring on another 'me too' programme on the floor, and in the process, scaling newer peaks of inanity. 20 young girls are competing to win 2 (unknown, average-looking, one of them being an epitome of uncouthness) guys in an attempt to find what they think is true love. How? Well, by dancing on tables, baring their bodies and god oh god, going to the extremeties of uncivic behaviour...its a pain to even discuss any more. But what's more, the show has an amazing TRP, is extremely popular and has had me glued to the TV sometimes (though for different reasons: i like to follow how and to what levels of uncouthness people of my age can go to, to win that chance to be a VJ).

Like I have said earlier, WE ARE A VOYEURISTIC PEOPLE, and its not just us in India. The formats for most of these shows are less bolder copies of what's been tried and tested in that mecca of television/film entertainment, the US.

(I did manage to catch up on a great documentary on the Roman Emperors in The History Channel-one of the few saving graces that still lends TV some respect. But they are few and very badly advertised, so you see...)

And yes, there's a new rendition of the Mahabharata on air, courtesy the Ekta Kapur family. The new stylised look really has my curiosity piqued, hope the actual drama is as sleek as the trailers are. However, a Ganga in semi- mordern turquoise blue jewellery may be a bit too much for the aam junta to stomach. But then, its (K)ekta, so lets just see.

Oh, education seems to be the latest parameter of status amongst the town-based upper-middle class. A fresh add-on to the boost in consumerism, is it? Pay some money and ship your child off to some school/college in a fancy hill station, so what if its the mid term? Oh and yes, the kewl factor comes from saying "my kid's studying in la-la-land". You see, the school/college's name is too bleak to be remembered. My honest doubts if the parents remember them!! Yeah yeah, I know, its not a new thing, this buying seats in fancy places: what IS new is the growing urgency among town-based uppermiddle/ midle class people to fall in line. Sheez, takes away the right to snigger at those "bade baap ke aulaads", yaar!!

Speaking of education, just took a new course, in the form of Amitav Ghosh's "The Glass Palace". Unlike most other contemporary writers, the man holds magic in all his works...and I'm talking of the 'meets-your-expectation' level that happens when a reader, fascinated with one work, goes on to another. Hosseini failed to meet it, Coelho seems, in his own way, erratic, but Ghosh, now that's a man who knows his mind, and exactly how to execute what's on it! Can't wait to start on his latest "The sea of popppies". And before anyone even thinks of doing it, a word of warning: DO NOT, PLEASE DO NOT say, "why, sheldon and dan brown do it always". For one, they do not, and more importantly, it's sacrilege to compare the two kinds of writing.

My life recently has been revolving a lot around numbers. For all the days of business journalism classes that I spent in bed, someone somewhere was making a note. And He, in his great sense of humour, has thrown me right in the center of business and journalism, in that order. As a correspondent(equities) in a global news agency. Huh, who would have thought?

Well, will wrap up now... just a parting thought: how is it that most girls and guys today, i.e, ones in the age group of 19-25, all somehow look, talk, think, and carry themselves in exactly the same way? The number of clones that surround one makes it almost impossible to remember names, identities. Someone should find a generic term for all of them!!

Thursday, May 15, 2008

B E M U S E D.totally.

Blogging seems to have gained a new status these days..Mr. Bachchan's doing it, SRK does it, and now, Amir Khan is doing it..to tell the world that his caretaker owns a dog that's the namesake to the king khan, no less!! And since our famed country of the billion worships almost anything that the stars of the silver screen do, well, what can I say? Chuck all your games, DVDs, Ipods out of the window...it's blogging all the way!! Who's the father of blogging? My deepest condolences to him/her ( ok..the mother, in that case) ...or has blogging finally achieved its aim?

Well, well, on a more pleasant note: "what's the english name of the vegetable commonly known in hindi as aalubukhara?" Yes darlings, we are talking of Panchvi paas..blah blah...

Oho, and the question was categorised under the subject "English", mind it!! :) Times, they ARE a changing, aren't they? Need i say more? Good luck SRK. I have immense respect for your energy and dedication, as much as meets my common eye..but please.....can we get a break from precocious 10 year olds payed to smile inanely into the screen, and weird contestants who claim: 1. to be "top model"s 2. that the capital of Pakistan is Istanbul? Please?

Indian thrillers ( the movie variety) have finally come of age. RACE is a fabulous conjencture by the famed duo of Bollywood thrillers, Abbas-Mastan ( is that how they still spell their names, or has the numeroblahblah bug gotten to them too?). Infact, this cross between Sidney Sheldon and Robin Cook with dashes of Ludlum and The Bold and the Beautiful thrown in between has turned out to be a potent and mind numbing cocktail of entertainment...full paisa wasool, and you don't mind the fact that characters like Miss Kaif and Miss Reddy cannot act to save their souls.

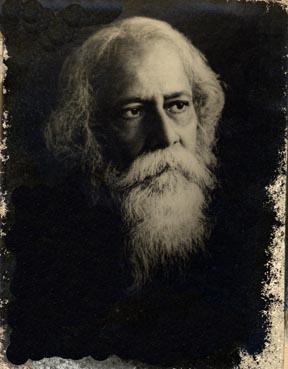

Oh, we ( as in the Bongs of the world) celebrated 25th Baisakh, that generally corresponds with the 9/10 of May every year once again, with much love and respect for the Grand Old Man of Indian Literature. Righto, it was Tagore's birthday. And to commemorate it, Eden Gardens in Kolkata saw a celebration of the same prior to the IPL match scheduled for the day, complete with SRK joining in for the rendition of the national anthem ( it was written by Tagore, you dorks!!:)) And guess what? The Knight Riders won the match..after a long spell of defeats. So there. What say? A little respect for our own people, and our tradition has never done any harm, has it? Speaking of which, yours truly's reminded of the great enthusiasm and love with which neighbourhoods arranged for their own cultural nights to commemmorate the same. A long time spent away from home had rusted the memories of these enthusing efforts: the long hours of rehearsals, the practice sessions, and then, finally, the final show: renditions of poetry, songs, dances, dance dramas, dramas written and choreographed by the Great Tagore. My humble respects to him.

As I wait for this peaceful lull to end in the general torpidity we call "life", I relive my childhood and savour the everyday happiness of HOME: the happiness of being woken by my maa, of asking for money of baba to buy that book, of fighting with my brother, of turning the volume down before granpa comes home:) And suddenly, I don't want to leave anymore...

Oh and in case you are still wondering, an aalubukhara is called a plum in english. Main paanchvi PASS hoon.

Saturday, March 29, 2008

dhoop ...

khidki se chan kar aati halki bhini si dhoop..main ... baithi hun apne us kone main...khidki ke us kone main jahan meri aankhon ke saath khelti hai dhoop...perchaiyan banti hain bigadti hain...mere aas paas cheezein badalti hain..log badalte hain... aate hain jaate hain...apne saath bahut kuch late hainkuch chod jate hain.. kuch apne daaman main samet kar le jate hain...main baithi hui apne daaman ko dekhti hun..us main har rang se sarabor khilkhilati hai dhoop....khidki se chan kar aati hai dhoop...

- gunjan singh

Friday, March 28, 2008

FLUX

A lot of lessons that demand a lot of questions and a lot of answers. Why is it that childhood friendships are never recreated in later phases of life? And why, oh why is it that the few people that you think you can look up to end up to be great dissapointments? Is it because the child's mind is easily impressionable, or because the burden of this rigour sucks out the charm of idealism? Or idolatry for that matter. Oh but that is another story....

A lot has been taken from me too....wiped out in the senseless mire of the de rigeur, till the final 'why' surfaces. But life is, sadly, not the sublime literature that the greats create. So, instead of stopping and turning life round on its hinges, the 'why' only serves to make it worse. Like Plato's cavemen who are happy cooped up residents of the black cave till one of them see a glimpse of the world outside, one slips into a deeper sense of abyss....damned are those who have asked, 'WHY?'

Where then, lies the answer? What then, is the solution? One might never know, I am afraid. The snows that lure the residents of the plains more often than not turn out to be a wet soggy mess....the whiteness does not allure then. A few prized friendships and a few reshuffled ideals are all that one is left with at the end of the journey...only to continue to find life ahead, in a new start. We are all phoenixes, aren't we?

Cheers to life, then!

where the mind is without fear and the head is held high..